“Shock” is one of the most frequently used words in a small animal emergency room and ICU. Despite this fact, a lot of veterinary students and new graduates have only superficial understanding of this term. This lack of understanding may lead to inaccurate diagnosis and mismanagement of patients in shock.

When using a very broad definition of “shock”, it is defined as inadequate cellular energy production or oxygen utilization by the tissues. In other words, cells are incapable of producing ATP molecules due to one or more of these factors (Dibartola 2011):

- Reduced blood flow (perfusion) to the tissues → circulatory shock

- Decreased oxygen content or arterial blood (e.g. methemoglobinemia, carbon monoxide toxicity, severe anemia) → hypoxic shock

- Intracellular energy production malfunction and/or mitochondrial dysfunction (e.g. severe hypoglycemia, cyanide toxicity) → metabolic shock

The circulatory shock is the category of shock that is most commonly referred to as “shock” in daily small animal clinical practice. It is important to understand that circulatory shock is a clinical diagnosis, and there is no perfect test that can be run to definitively rule it in. It is a common misconception that low arterial blood pressure (arterial hypotension) is always present in patients with shock. In reality, canine and feline patients in shock may have low, normal or even transiently elevated blood pressure during the early compensated stage of circulatory shock (Porter et al. JVECC 2013).

So, how do I teach veterinary students to recognize a circulatory shock (i.e. a global state of hypoperfusion = an inadequate blood flow to the various body tissues)?

To make a clinical diagnosis of circulatory shock, one needs to evaluate 6 “core” perfusion parameters +/- obtain supplemental information:

- Mentation

- Heart rate

- Pulse quality

- Rectal and distal extremities temperature

- Mucous membrane color

- Capillary refill time

Supplemental parameters that can aid in a diagnosis of shock:

- Non-invasive or invasive blood pressure

- Serum or plasma lactate

- Shock index (HR/BP systolic)

- Urine output in a patient with intact renal function

- Central venous oxygen saturation (ScvO2)

For each of these findings, one can assign a “price” (see Table 1). Once the patient accumulates >20 cents, the diagnosis of shock should be suspected. If your patient accumulated >=40 cents, shock is VERY likely (i.e. high specificity, low sensitivity). Patients that “earned” only 20 cents are in a gray zone (i.e. low specificity, high sensitivity). If a patient accumulated <20 cents, the diagnosis of shock is VERY UNLIKELY.

| Perfusion parameters | Abnormal result associated with shock | “Price” |

| Mentation | Decreased (dull, stuporous) | 10 cents |

| Heart rate | Typically tachycardic (cats specifically and dogs with decompensated shock may be bradycardic) | 10 cents |

| Pulse quality (bilateral) | Decreased (fair, poor, absent) | 10 cents for fair or poor, 20 cents for absent |

| Rectal and distal extremities temperature | Typically hypothermic (however, patients with septic shock may be “warm”) | 10 cents |

| Mucous membrane color | Pale, pale-pink, gray (patients with distributive shock may be hyperemic = bright red gums) | 10 cents for pale-pink and 20 cents for pale or gray |

| Capillary refill time | Typically >2-3 sec, may be shortened in distributive shock | 10 cents |

| Non-invasive or invasive blood pressure | <90 mmHg systolic or <60 MAP if decompensated shock; may be normal or mildly elevated during compensated stage | 20 cents for arterial hypotension |

| Serum or plasma lactate | >2.5-3 mmol/L | 10 cents if lactate 2.5-4 mmol/L; 20 cents for >4 mmol/L |

| Shock index (HR/BP systolic) | >0.9 in dogs; >1.6 in cats (limited evidence; Kenton 2016) | DOGS: 10 cents for SI = 1-2; 20 cents for SI >2 CATS: 10 cents for SI >1.6 |

| Urine output in a patient with intact renal function | <1 ml/kg/hour with USG >1.030 | 10 cents |

| Central venous oxygen saturation (ScvO2; obtained from the central catheter) | <65% | 10 cents |

There are several reasons why a single abnormal perfusion parameter is not sufficient to diagnose circulatory shock with confidence:

- There are a lot of other disease processes that can cause these abnormalities

- A single measurement may be inaccurate or artifactual

Consider a clinical scenario #1: You are presented with a 15-year-old spayed female cat that has been historically diagnosed with Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD IRIS stage 3). She presented to you due to progressive weight loss, however she is still eating okay and her behavior has not changed. Your physical examination with respect to her perfusion parameters revealed the following findings:

- Mentation: normal

- Heart rate: 200 bpm

- Pulse quality: strong

- Rectal and distal extremities temperature: 98.9 F (Reference: 99.5-102.5F)

- Mucous membrane color: pale

- Capillary refill time: 1 sec

Supplemental parameters:

- Non-invasive blood pressure: Doppler 170 mmHg

- Serum or plasma lactate: 2.4 mmol/L

- Shock index (HR/BP systolic): 1.17

- Urine output in a patient with intact renal function: not evaluated

- Central venous oxygen saturation (ScvO2): not evaluated

ASSESSMENT: this feline patient “earned” 20 cents (a gray zone). Considering her unchanged appetite and behavior, a circulatory shock is not very likely despite the presence of abnormal rectal temperature and mucous membrane color. Her decreased rectal temperature may be explained by CKD-related muscle wasting and azotemia (Kabatchnick et al. JVIM 2016). Her pale mucous membranes are explained by a PCV of 20% secondary to her CKD-related chronic non-regenerative anemia.

Consider a clinical scenario #2: You are presented with a 2-year-old neutered male Labrador that was hit by a car 30 minutes prior to the presentation to your hospital. Initial triage examination showed the following results:

- Mentation: dull

- Heart rate: 170 bpm

- Pulse quality: strong

- Rectal and distal extremities temperature: 101.1 F (Reference: 99.5-102.5F)

- Mucous membrane color: pink

- Capillary refill time: 2 sec

Supplemental parameters that can aid in a diagnosis of shock:

- Non-invasive or invasive blood pressure: Doppler 100 mmHg

- Serum or plasma lactate: 3.1 mmol/L

- Shock index (HR/BP systolic): 1.7

- Urine output in a patient with intact renal function: not evaluated

- Central venous oxygen saturation (ScvO2): not evaluated

ASSESSMENT: this canine patient “earned” 40 cents (dull mentation, elevated HR, hyperlactatemia, and elevated shock index). Despite the fact that his blood pressure remained within normal limits and pulses were strong, there is enough evidence to conclude that this patient was in a compensated phase of shock. If the cause of shock is not recognized and addressed in a timely manner, the dog may continue to decompensate.

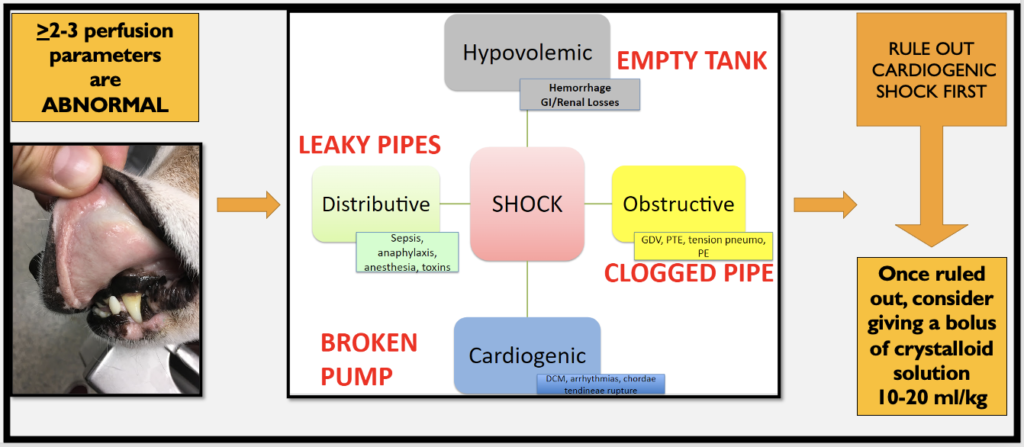

It is important to note that there are 4 different types of circulatory shock:

- Hypovolemic

- Obstructive

- Distributive

- Cardiogenic

Regardless of the type of shock, the majority of small animal patients in shock will present with non-specific clinical signs (see Table 1). When the type of shock is not apparent, it can be called “undifferentiated”. A veterinarian must determine the type of shock as soon as possible to choose the most appropriate resuscitation strategy (Figure 1), however this is beyond the scope of this blog article.

The Bottom Line

During every triage examination of a small animal patient, six perfusion parameters should be evaluated. The presence of at least 2 or 3 abnormalities should increase the index of suspicion for undifferentiated shock in this animal. These findings should prompt a clinician to perform further evaluation of the patient in a timely manner and diagnose the type of shock to choose the most appropriate resuscitation strategy.

Watch the video version here:

References

- Fluid, Electrolyte, and Acid-Base Disorders in Small Animal Practice. 4th Edition. Author: Stephen DiBartola 2011.

- Porter AE, Rozanski EA, Sharp CR, Dixon KL, Price LL, Shaw SP. Evaluation of the shock index in dogs presenting as emergencies. J Vet Emerg Crit Care (San Antonio). 2013 Sep-Oct;23(5):538-44. doi: 10.1111/vec.12076. Epub 2013 Jul 15. PMID: 23855723; PMCID: PMC3796026.

- Kenton. An evaluation of the shock index in cats with hypoperfusion; a novel, pilot study (BSAVA congress proceedings 2016).

- Kabatchnick E, Langston C, Olson B, Lamb KE. Hypothermia in Uremic Dogs and Cats. J Vet Intern Med. 2016 Sep;30(5):1648-1654. doi: 10.1111/jvim.14525. Epub 2016 Aug 2. PMID: 27481336; PMCID: PMC5032875.

One thought on “How to teach veterinary students to diagnose shock?”