A 7-month-old female spayed domestic shorthair was presented to an emergency service (ER) for increased respiratory rate and effort. The cat got spayed at her primary veterinarian 6 days prior to this episode, and had been doing well otherwise up until the evening of presentation. The owner reported no previous medical conditions.

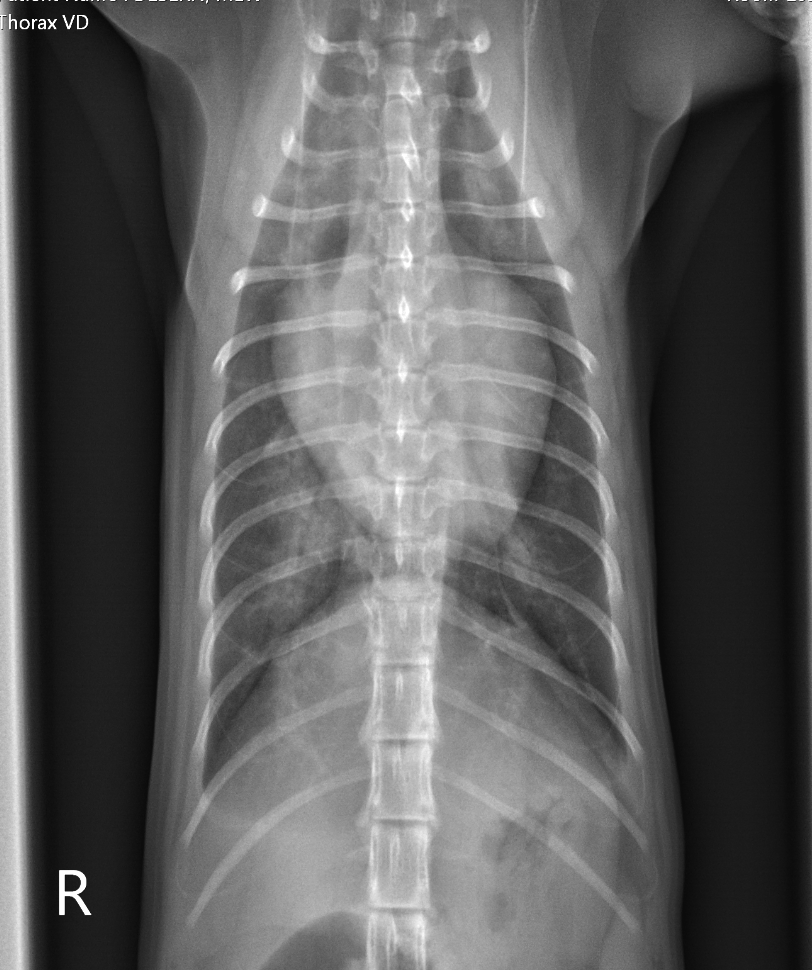

The initial triage examination showed tachypnea and moderately increased respiratory effort with increased bronchovesicular sounds in dorsal lung fields. No heart murmur or other abnormal physical examination findings were noted at that time. An emergency clinician performed thoracic radiographs (Figure 1 and 2) and point-of-care blood work that was within normal limits.

The attending veterinarian misinterpreted thoracic radiographs and concluded that the patchy interstitial lung pattern was likely due to pneumonia. No additional diagnostics were performed, and the cat was sent home with an oral antibiotic and subcutaneous fluids.

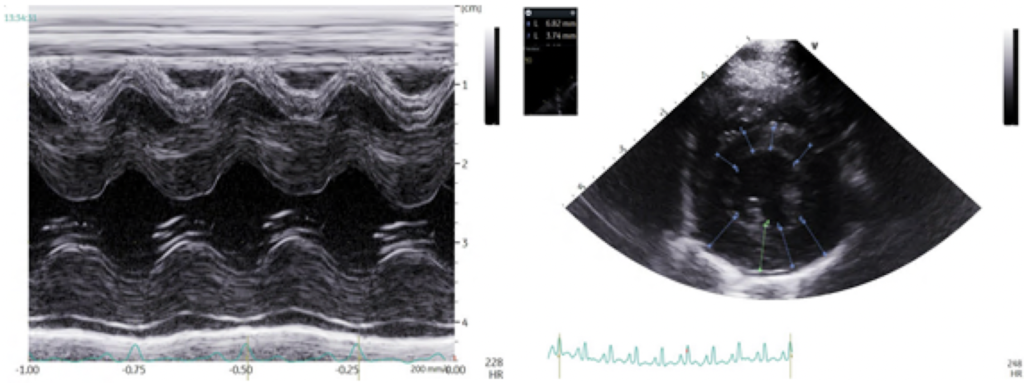

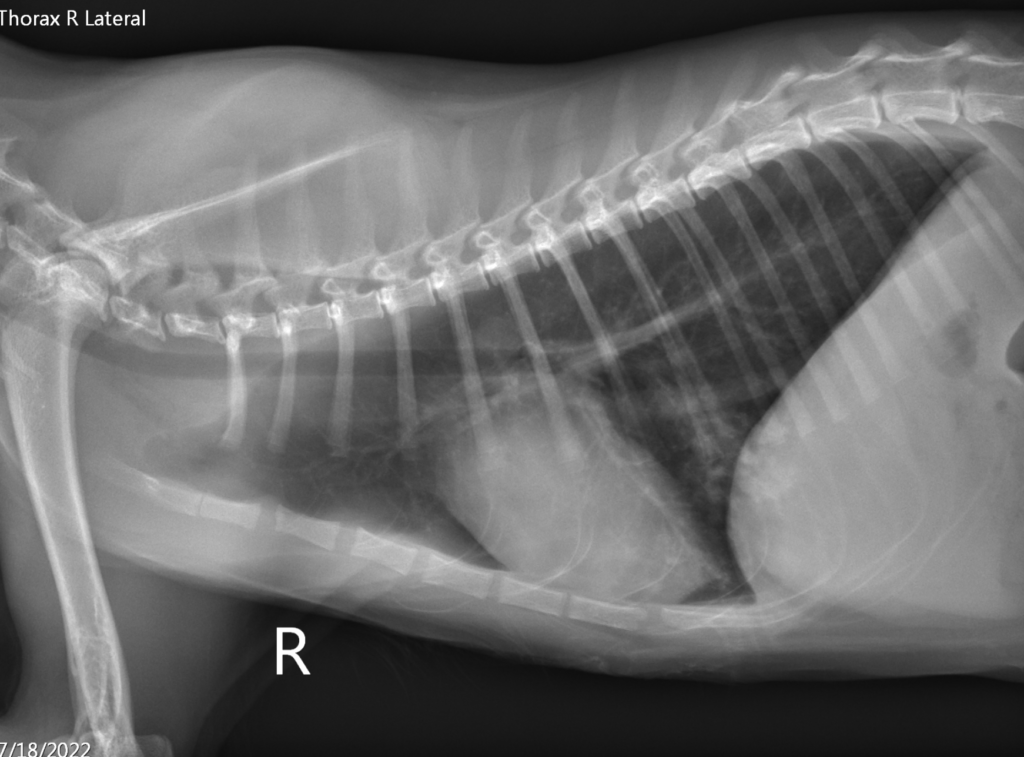

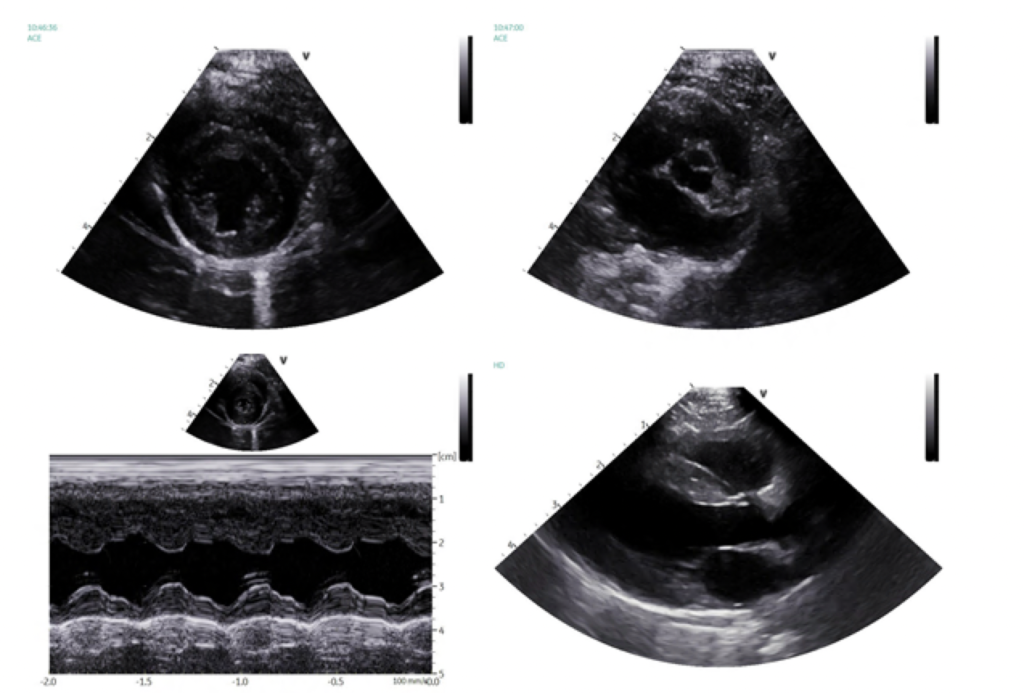

The patient represented to the same ER 12 hours later due to not improving respiratory effort and progressive lethargy. At this time, the cat had bilateral crackles on lung auscultation, and was hypothermic at 98F (36.6C). Point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) showed enlarged left atrium in conjunction with diffuse bilateral infinite B lines, and repeat thoracic radiographs demonstrated similar generalized cardiomegaly, persistent interstitial infiltrates and mild pulmonary venous distention. After initial stabilization with oxygen therapy, intravenous furosemide and butorphanol, a full echocardiogram was performed (Figure 3) that showed moderately thickened left ventricular free wall (i.e. HCM phenotype), normal systolic function, and moderately enlarged left atrium.

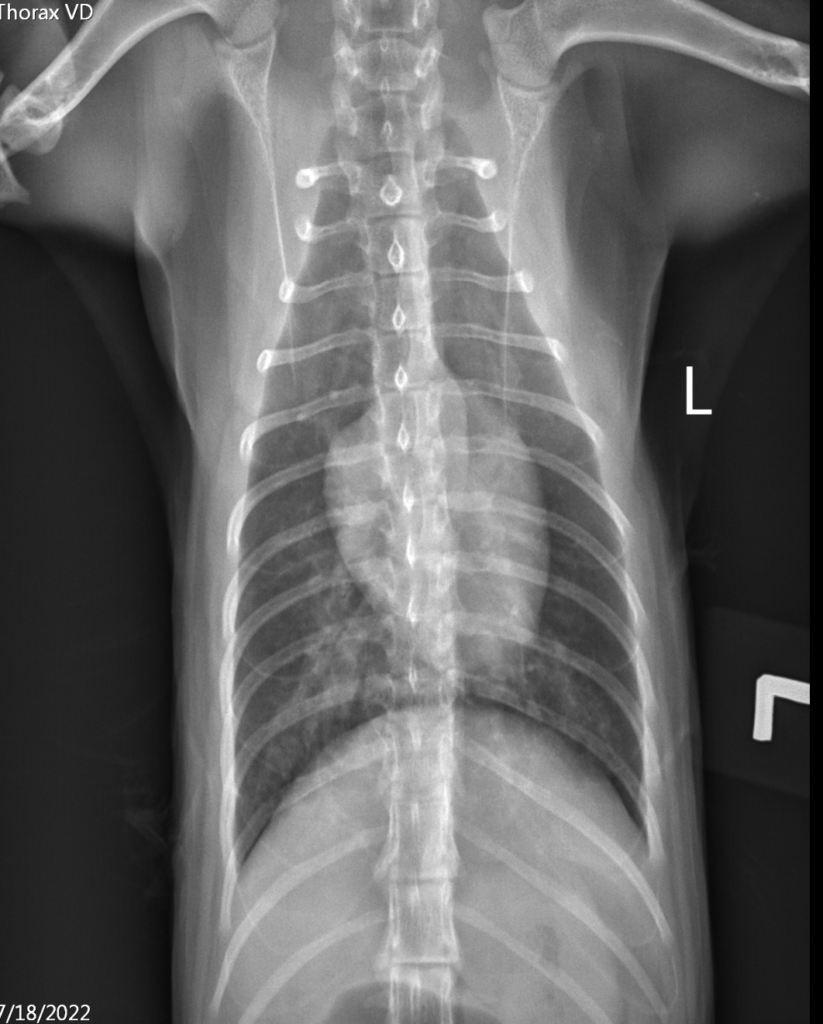

The differential diagnoses for increased LV free wall thickness included transient myocardial thickening, myocarditis and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM). The cat was hospitalized and treated for congestive heart failure (CHF). She responded well to therapy, and her recheck thoracic radiographs (Figure 4 and 5) revealed resolving CHF. She tested negative for FeLV/FIV and heartworm disease (HWD).

Repeat echocardiographic examination two weeks later revealed a structurally normal heart with normalized LV wall thickness and left atrial diameter (Figure 6). The cat has done well at home and was back to normal.

So, why is it so important to differentiate between true HCM (hypertrophic cardiomyopathy) vs. transient myocardial thickening and myocarditis?

When a feline patient presents with signs of CHF and has evidence of thickened LV wall (>=6 mm) in association with enlarged left atrium, all of the following 3 differentials must be considered: HCM, transient myocardial thickening and myocarditis.

There are 5 main pathophysiologic mechanisms that may lead to increased thickness of the myocardium:

- An increase in mass of individual myocytes and interstitial fibrous connective tissue (i.e. myocyte hypertrophy or hyperplasia typical for true HCM);

- Intracellular accumulation of metabolic products (e.g. secondary to a storage disease such as amyloidosis);

- Interstitial infiltration with proteins or fluid/edema (e.g. secondary to myocarditis)

- Interstitial infiltration with neoplastic cells (e.g. feline lymphoma);

- Pseudohypertrophy as a stand-alone cause of increased myocardial thickening that occurs secondary to severe dehydration/hypovolemia.

Transient myocardial thickening (TMT) is a condition mimicking HCM during initial presentation, however, as opposed to the true HCM that typically is associated with a poor long-term prognosis, cats with TMT have a reverse remodeling of the heart muscle with normalization of cardiac structure and function.

In a recent retrospective study by Matos et al. (JVIM 2018), authors described 21 feline patients with suspected TMT that were compared to control cats with HCM. They found that cats with TMT were younger (median age of 2 years) than cats with HCM (median age of 8 years). Also, significantly more cats with TMT than HCM had stressful events (e.g. a spay surgery) preceding their presentation in congestive heart failure (71% of TMT versus 29% of HCM cases). Stalis et al. (Vet Pathol 1995) described very similar stressful events preceding the development of CHF in 21/28 (75%) of young cats with endomyocarditis that was diagnosed on necropsy.

The underlying cause of transient myocardial thickening is not known but myocardial edema and transient cellular infiltration with inflammatory cells (e.g. due to myocarditis) is the most likely explanation. Many cats received drugs before presenting with TMT (e.g. sedation/anesthesia drugs for spay or neuter surgery), and hypersensitivity drug reactions have been reported as a cause of myocarditis in human patients (Kuchynka et al, Biomed Res Int 2016). Another interesting hypothesis is that a catecholamine surge caused by a stressful event may cause similar myocardial changes. In people, a condition known as Takotsubo cardiomyopathy is believed to be caused by stress or life-changing events (e.g. a death of a family member). Catecholamines released by pheochromocytoma have also been implicated in causing toxic myocarditis (Ferreira et al. J Am Coll Cardiol 2016).

Given a strong likelihood of myocarditis being a potential cause of TMT in cats, it may be reasonable to perform the following diagnostic tests in cats suspected to have TMT:

- Cardiac troponin I (cTnI)

- FeLV/FIV testing

- Serological testing for Toxoplasma and Bartonella

The cat described in this blog article was tested positive for Bartonella and had extremely elevated cTnI levels that got normalized 2 weeks later which was suggestive of myocarditis. cTnI might be useful to differentiate TMT vs. true HCM cases, although there could be some overlap between these two groups.

The Bottom Line

It is very important to remember that not all cats with thickened LV walls (HCM phenotype) will have true Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. The prognosis is better in cats with CHF associated with transient myocardial thickening than HCM.

Download my free cheat sheet on treatment of cardiogenic pulmonary edema in dogs and cats here.

Watch the video version here:

References

- Novo Matos J, Pereira N, Glaus T, Wilkie L, Borgeat K, Loureiro J, Silva J, Law V, Kranjc A, Connolly DJ, Luis Fuentes V. Transient Myocardial Thickening in Cats Associated with Heart Failure. J Vet Intern Med. 2018 Jan;32(1):48-56. doi: 10.1111/jvim.14897. Epub 2017 Dec 15. PMID: 29243322; PMCID: PMC5787177.

- Stalis IH, Bossbaly MJ, Van Winkle TJ. Feline endomyocarditis and left ventricular endocardial fibrosis. Vet Pathol. 1995 Mar;32(2):122-6. doi: 10.1177/030098589503200204. PMID: 7771051.

- Kuchynka P, Palecek T, Masek M, et al. Current diagnostic and therapeutic aspects of Eosinophilic myocarditis. Biomed Res Int 2016;2016:2829583.

- Ferreira VM, Marcelino M, Piechnik SK, et al. Pheochromocytoma is characterized by catecholamine‐mediated myocarditis, focal and diffuse myocardial fibrosis, and myocardial dysfunction. J Am Coll Cardiol 2016;67:2364–2374.

3 thoughts on “Do All Cats with “HCM” have HCM?”