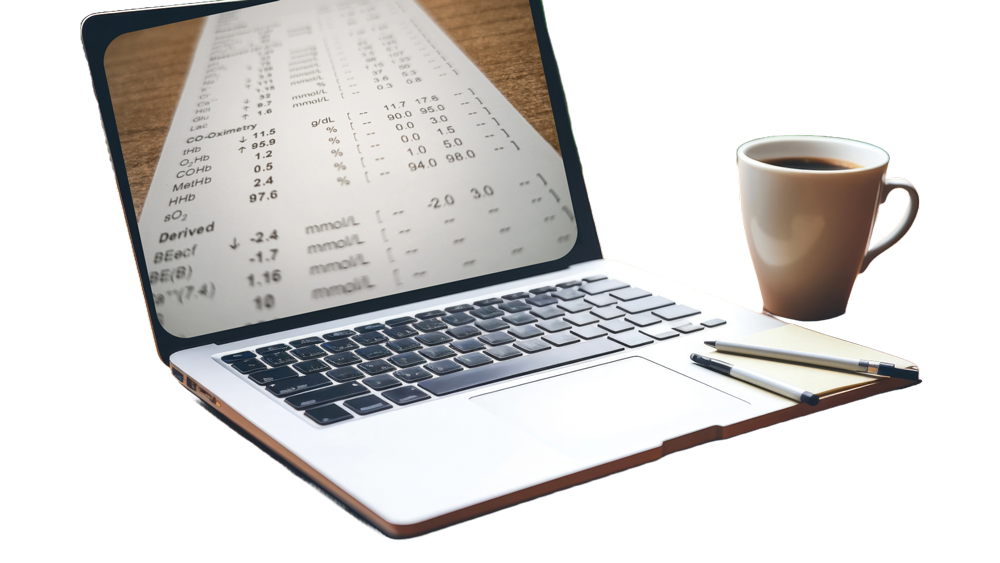

This blood gas analysis training for emergency veterinarians, interns, residents, and ECC or anesthesia technicians delivers a focused, interactive, and retention-driven approach to mastering acid–base and electrolyte disorders. Unlike traditional CE courses, webinars, or lectures—often long, passive, and quickly forgotten—this program uses short, targeted lessons, real-life emergency case scenarios, active learning quizzes with feedback, and a collaborative community to keep you engaged and ensure lasting knowledge.

You’ll also gain access to our Emergency Electrolyte and Acid–Base Calculator, allowing you to perform rapid, accurate supplementation calculations and full acid–base interpretation in seconds, giving you the confidence to apply what you’ve learned immediately in critical situations.

Over the last 15 years, I have attended dozens of CE events and watched hundreds of hours of webinars, only to realize a week later that I can recall only 5-10% of this information. Have you ever felt that way?