In the field of veterinary medicine, standard clotting tests like prothrombin time (PT) and partial thromboplastin time (PTT) have traditionally been used to diagnose hypocoagulability, or a decreased ability of the blood to clot. However, recent research has raised the question of whether both prolonged and shortened PT/PTT can actually be indicative of hypercoagulability, a state where there is an increased tendency for blood clot formation.

Let’s first explore the findings related to shortened PT/PTT as an indicator of hypercoagulability. A retrospective case-control study conducted on 23 dogs examined their clotting times and thrombotic tendencies (Song et al. JVECC 2016). The study included dogs with shortened PT/PTT as well as dogs with normal PT/PTT as the control group. The researchers also measured thromboelastography (TEG) parameters alongside the clotting times.

The results of the study showed that dogs with shortened clotting times had a higher prevalence of thrombus formation and suspected pulmonary thromboembolism (PTE). Additionally, these dogs had a higher mean concentration of D-dimer, a marker of blood clot breakdown. Interestingly, there was no statistical difference in TEG parameters between the two groups.

While this research is intriguing, it is important to acknowledge the limitations of this study. Being a retrospective study, it is challenging to control for various confounding factors that may influence the results. Moreover, the outcome of thrombus formation was based on documented catheter thrombosis episodes, which means that only cases with documented clots were considered. This may lead to an underestimation of the true thrombus formation rate. It is also worth noting that factors unrelated to hypercoagulability, such as catheter size or location, could contribute to catheter thrombosis.

Now, let’s delve into the possibility of prolonged PT/PTT being associated with hypercoagulability. When patients develop macro- or microthrombosis, they continue to consume clotting factors and platelets, leading to a mild to moderate prolongation of clotting times and a reduction in platelet count. This can result in prolonged PT/PTT values (i.e. consumptive coagulopathy in the face of thrombosis).

To differentiate between hyper- and hypocoagulable states in patients with prolonged PT/PTT, several factors can be considered. First, the degree of prolongation should be assessed. Patients with consumptive coagulopathy tend to have mild to moderate PT/PTT prolongation as opposed to other more severe coagulopathies (e.g. anticoagulant toxicity or liver dysfunction).

Additionally, the platelet count can provide valuable information. Pets with active consumptive process will use up their platelets along with clotting factors to form new clots. The presence of mild to moderate thrombocytopenia may further support suspected consumptive coagulopathy.

The presence of macrothrombosis or the development of organ dysfunction secondary to presumed microthrombosis can also indicate a hypercoagulable state. In addition, performing viscoelastic testing in conjunction with a coagulation panel can provide insights into the overall coagulation status and help determine if a hypercoagulable tracing is present.

Finally, the positive response to antithrombotic therapy in patients with prolonged PT/PTT and/or thrombocytopenia may give you a hint that the cause of these derangements was excessive consumption. Recently, I managed a 10 year-old Labrador with portal vein thrombosis and suspected consumptive coagulopathy resulting in moderate thrombocytopenia and mild prolongation of PT/PTT. Within 7 days after the dog was started on rivaroxaban and clopidogrel, his coagulation parameters and platelet count had completely normalized. This type of response further supported our theory that his coagulation derangements were caused by active consumption.

Disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) is considered one of the most common causes of consumptive coagulopathy. It is a condition where there is excessive activation of the coagulation system, resulting in the consumption of clotting factors and platelets. It is a serious complication that arises as a result of an underlying disease or injury, leading to an imbalance in pro- and anticoagulant factors and crosstalk between the coagulation and inflammatory systems. DIC always requires a trigger, and several conditions can act as potential triggers. Extensive surgical trauma, sustained shock, systemic inflammation or sepsis, and underlying malignant diseases are some of the common triggers associated with DIC. Understanding the underlying cause is crucial for effectively managing and treating DIC.

The development of DIC is a dynamic process. It begins with the hyperactivation of the coagulation system, leading to the formation of micro- or macrothrombi. However, diagnosing microthrombosis in the early stages of the disease is challenging, often resulting in DIC being considered only when visible thrombi are present or organ dysfunction becomes apparent. The widespread hypercoagulation and thrombosis in DIC lead to the consumption of platelets, fibrinogen, and other clotting factors, ultimately leading to consumptive coagulopathy and bleeding disorders.

Diagnosing DIC is a complex task, and there is no definitive gold standard for its diagnosis. In the literature, expert panels are commonly used as a reference for diagnosing DIC (Goggs et al. JVECC 2018). However, there are also various scoring systems available for both human and veterinary medicine. These scoring systems typically rely on 5-6 blood work parameters, and to diagnose DIC, at least 3 out of the 6 parameters should be abnormal. These parameters include increased values of aPTT, PT, D-dimer concentration, as well as decreased levels of antithrombin, fibrinogen, and platelet count.

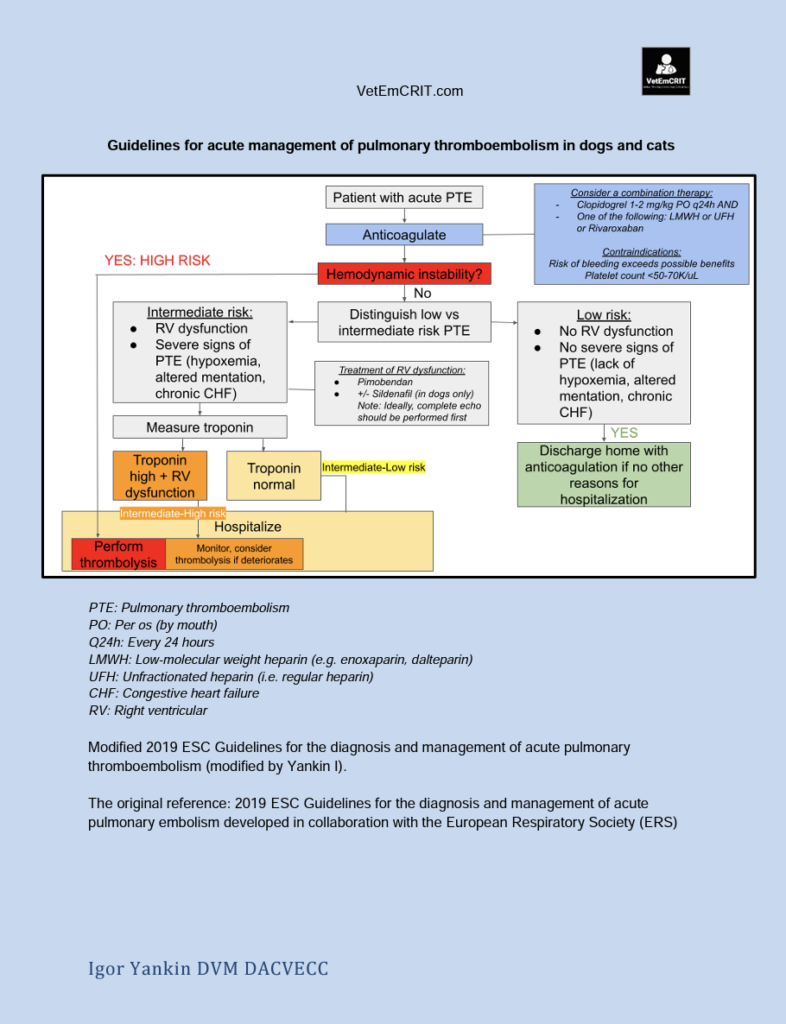

The treatment approach for DIC depends on the stage at which the patient is diagnosed. If DIC is detected in its early stages, before overt bleeding occurs, initiating antithrombotic therapy may theoretically help prevent further consumption of clotting factors and platelets, thereby averting severe bleeding. However, if significant bleeding is present, immediate intervention is necessary. Fresh frozen plasma can be utilized as a source of clotting factors to control life-threatening bleeding episodes.

It is essential to note that interpreting clotting tests can be complex, and the results should always be interpreted in the context of the patient’s clinical presentation, medical history, and other diagnostic findings.

The Bottom Line

While PT/PTT tests have traditionally been used to diagnose hypocoagulability, there is some signal that both prolonged and shortened PT/PTT values may be indicative of hypercoagulability. The use of additional diagnostic tools, such as viscoelastic testing, can provide valuable insights into the overall coagulation status of a patient.

References:

- Song, Jennifer et al. “Retrospective evaluation of shortened prothrombin time or activated partial thromboplastin time for the diagnosis of hypercoagulability in dogs: 25 cases (2006-2011).” Journal of veterinary emergency and critical care (San Antonio, Tex. : 2001) vol. 26,3 (2016): 398-405. doi:10.1111/vec.12478

- Goggs, Robert et al. “Retrospective evaluation of 4 methods for outcome prediction in overt disseminated intravascular coagulation in dogs (2009-2014): 804 cases.” Journal of veterinary emergency and critical care (San Antonio, Tex. : 2001) vol. 28,6 (2018): 541-550. doi:10.1111/vec.12777

2 thoughts on “Can both prolonged PT/PTT and shortened PT/PTT be indicative of a prothrombotic state?”