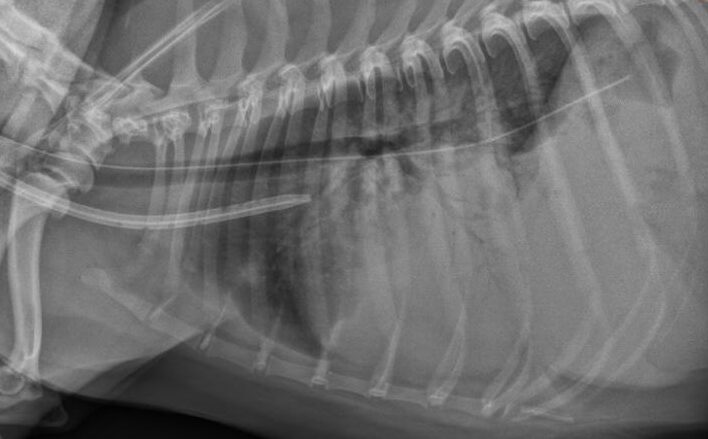

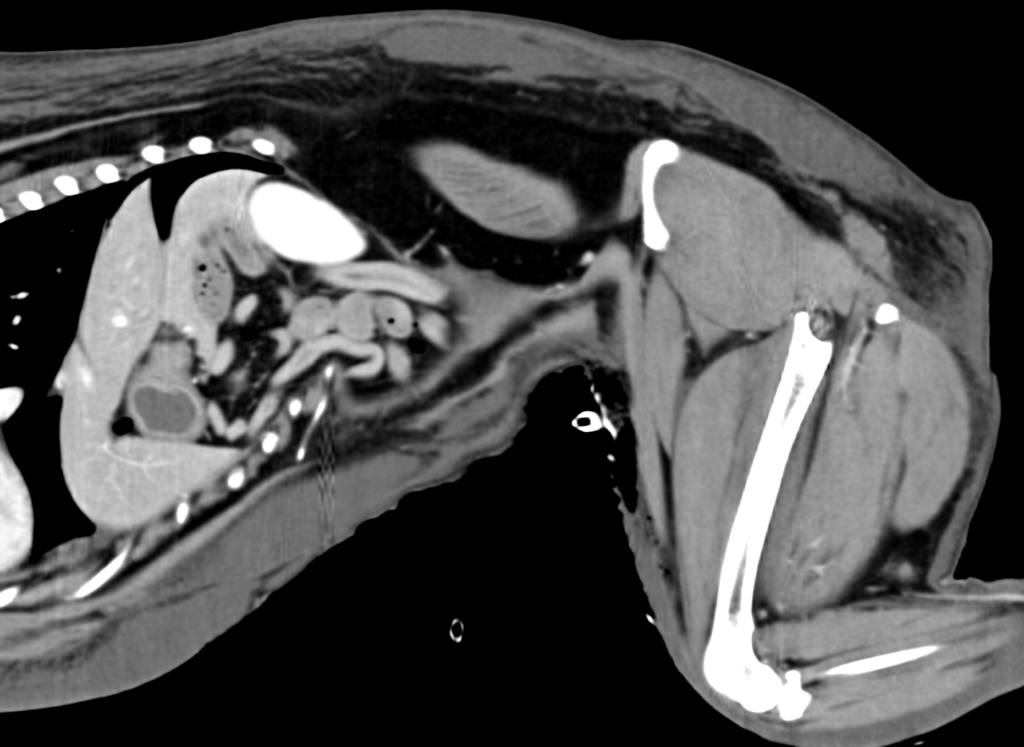

Nasogastric and nasoesophageal tubes are commonly used in small animal practice for short-term enteral nutrition. They are easy to place without general anesthesia, inexpensive and can be used for gastric decompression and drug administration.

Unfortunately, feeding tube misplacement happens much more frequently than the number of cases described in the literature. Although rare, misplacement may occur in advanced tertiary veterinary hospitals despite a strict adherence to the institutional policies and radiographic confirmation by board-certified veterinary radiologists (Rodriguez-Diaz JAAHA 2021).

Continue reading “Radiographic confirmation of NG/NE tube placement in dogs and cats: Is it truly foolproof?“