Acid-base analysis in a cat can be deceptively complex, especially when traditional parameters like pH, pCO₂, and bicarbonate appear normal. In this case, advanced analysis revealed a hidden mixed disorder that would have been missed without deeper evaluation.

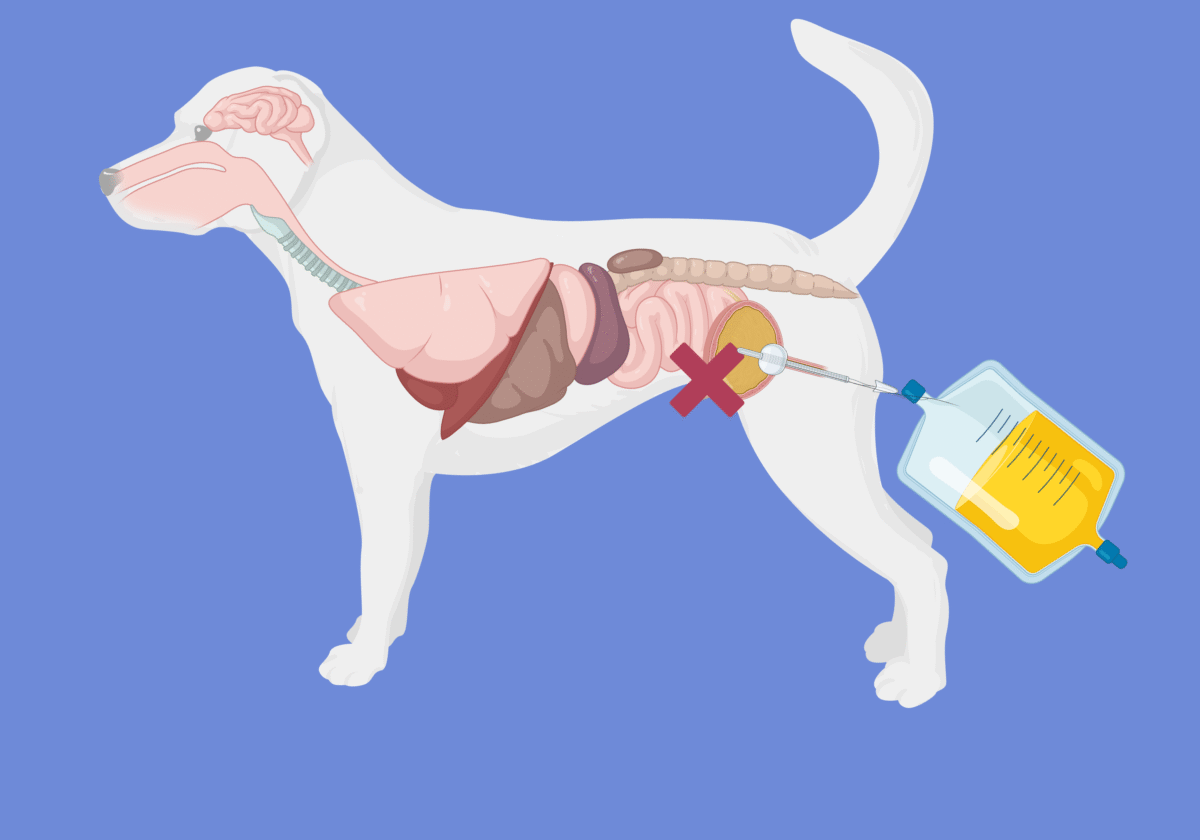

You are presented with a 12-year-old spayed female domestic shorthair cat with a history of injection-site sarcoma and diabetes mellitus. She is currently being treated with an SGLT2 inhibitor, a sodium–glucose co-transporter-2 blocker.

On physical examination, she was dull, dehydrated, and hypothermic.

A venous blood sample was obtained immediately after IV catheter placement. The collection was performed under strict anaerobic conditions, without struggling, and with no evidence of sampling error.

The venous blood gas panel was then analyzed, and the results are shown below.

- pH = 7.427 (Reference: 7.244 – 7.444)

- pCO₂ = 28.7 mmHg (Reference: 27.3 – 49.1)

- HCO₃⁻ = 19.11 mmol/L (Reference: 15.9 – 24.7; mid-normal: )

- Base excess (BEecf) = – 5.5 mmol/L (Reference: -10.4 to -0.5)

- Sodium = 137.4 mmol/L (Reference: 150.5 – 157.2; mid-value: 153.9)

- Potassium = 2.96 mmol/L (Reference: 3.11 – 4.64)

- Chloride = 95.9 mmol/L (Reference: 113 – 123; mid-value: 118)

- Ionized calcium = 1.15 mmol/L (Reference: 1.21 – 1.45)

- Glucose = 135 mg/dL, or 7.5 mmol/L (Reference: 74 – 159 mg/dL = 4.1 – 8.8 mmol/L)

- Lactate = 2.3 mmol/L (Reference: 0 – 3.3 mmol/L)

- Creatinine = 1.25 mg/dL, or 110.5 µmol/L (Reference: 0.8 – 1.8 mg/dL = 70.7 – 159.1 µmol/L)

- BUN = 20 mg/dL, or 7.1 mmol/L (Reference: 19 – 33 mg/dL = 6.8 – 11.8 mmol/L mmol/L)

- Anion gap = 25.4 (Reference: 14.8 – 23.8; mid-normal: )

- Albumin = 3.5 g/dL = 35 g/L (Reference: 2.2 – 4 mg/dL; mid-normal value: 3.1 mg/dL)

- Phosphate = 1.3 mmol/L = 3.9 mg/dL (Reference: 3.1 – 7.5 mg/dL; mid-normal value: 5.3 mg/dL)

Now, let’s apply the advanced traditional approach to this case to perform an acid-base analysis in this cat.