This blog outlines a practical, evidence-based approach to deciding when treatment for Enterococcus in septic peritonitis is truly warranted in dogs and cats.

A 7-year-old spayed female Persian cat was presented to an emergency service for evaluation of fever, chronic vomiting, and severe lethargy. On initial examination, the cat was stuporous, with fair femoral pulses, pale pink mucous membranes, moderate dehydration, a body temperature of 104°F (40°C), and a heart rate of 150 beats per minute.

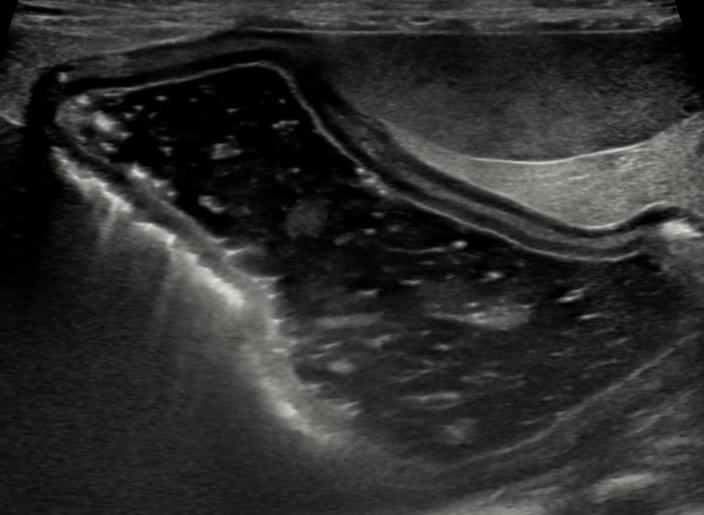

The initial work-up suggested septic peritonitis and partial jejunal mechanical obstruction, based on abdominal ultrasound and abdominal fluid cytology. Stabilization included fluid resuscitation and intravenous antibiotics (ampicillin/sulbactam at 30 mg/kg IV q8h and enrofloxacin at 5 mg/kg IV q24h), followed by norepinephrine (0.1 mcg/kg/min) due to persistent arterial hypotension.

Three hours after presentation, the cat underwent exploratory laparotomy, which revealed a foreign body in the jejunum causing obstruction and perforation. Post-lavage peritoneal swabs were submitted for culture and sensitivity. The cat received resection and anastomosis, along with JP drain placement. Norepinephrine was discontinued 36 hours post-surgery, and nasogastric tube feeding was initiated shortly thereafter.

Continue reading “3 Steps to Decide If You Should Treat Enterococcus in Septic Peritonitis”