In this post, we’re breaking down the latest data on conservative—meaning non-surgical—management of urinary tract rupture in dogs and cats.

We’ll compare a few recent studies and walk through a practical decision-making algorithm that you can actually use in clinical practice.

Surgery Has Been the Norm… Until Now

Historically, the words “urinary tract rupture” were nearly synonymous with “prep for surgery.” And that’s not just anecdotal—it’s backed by data. Multiple studies have shown that the vast majority of these patients—anywhere from 75% to 95%—undergo surgical repair depending on the study (Hornsey et al. JFMS 2021; Grimes et al. JAVMA 2018).

But here’s the thing: we now have a growing body of evidence showing that selected cases can heal with medical—or what we call conservative—management.

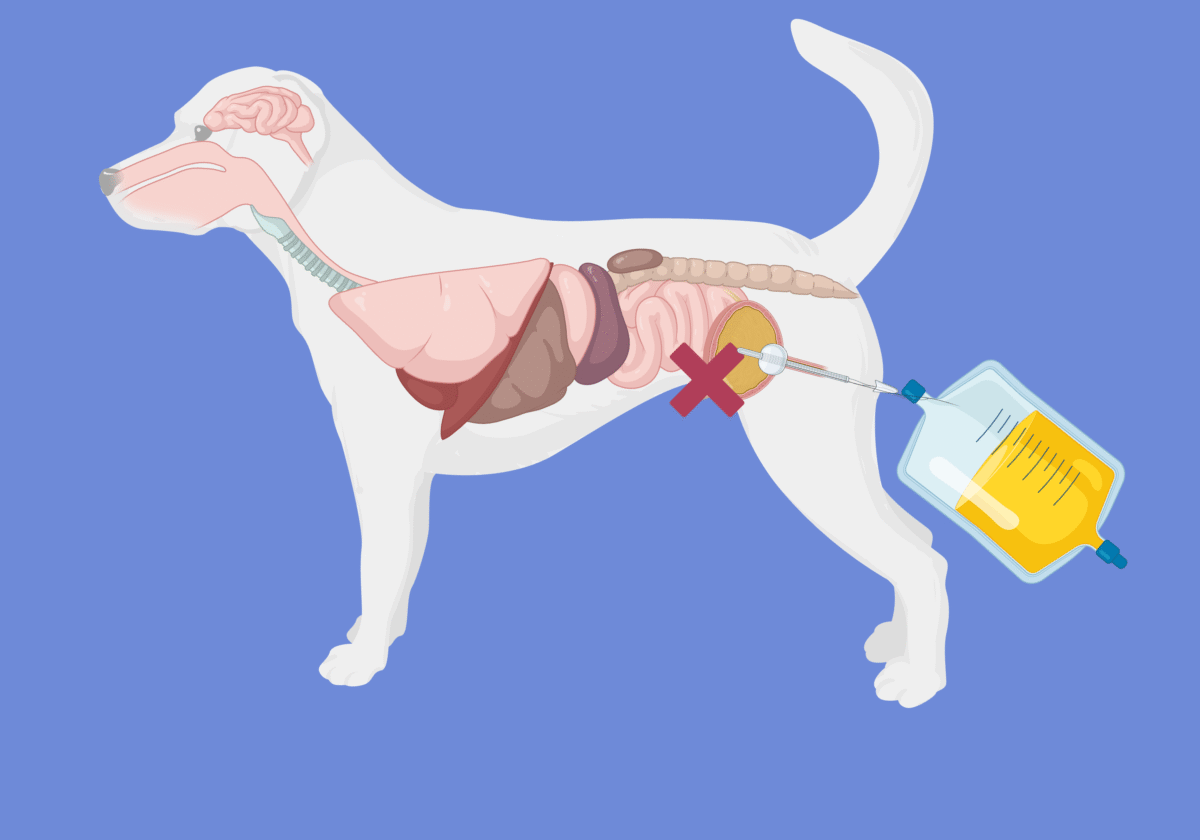

This approach typically involves placing a catheter or drain to divert urine away from the rupture site. This process, known as urinary diversion, reroutes urine so it doesn’t accumulate in places it shouldn’t, giving the body time to seal the leak.

New Data from the Royal Veterinary College (Toh et al. JSAP 2025)

A 2025 retrospective study out of the Royal Veterinary College in London looked specifically at conservative management. They documented 40 cats and 12 dogs with confirmed urinary tract rupture—all successfully managed without surgery (Toh et al. JSAP 2025).

It’s important to note that this RVC study only included animals that survived and were managed conservatively, so it doesn’t tell us how often conservative management fails. But it does demonstrate what’s possible.

Causes of Rupture

In this case series, the most common causes of urinary tract rupture in cats were urethral obstruction and catheterization (17/40 cases), followed by cystocentesis (14 cases). Only 5 cats had external trauma unrelated to medical procedures.

For the 12 dogs, cystocentesis, external trauma, and recent urinary tract surgery each accounted for 3 cases.

That means many of the ruptures in this study were iatrogenic, caused by medical interventions — very different from older studies where trauma (e.g., vehicular accidents) was the leading cause. For comparison, earlier studies reported trauma in 30–56% of uroabdomen cases (Schmiedt et al. JVECC 2001; Grimes et al. JAVMA 2018).

But in the RVC paper, trauma accounted for only 15% (8 of 52 cases).

This is an important nuance. External trauma cases might have been excluded because they weren’t attempted to be treated medically, or they began with conservative care but ultimately failed and required surgery.

Location, Diversion Strategy, and Duration

Bladder Ruptures

19 of the 52 cases involved bladder rupture.

- 16 were managed with urethral catheters

- 3 had abdominocentesis

- 5 received percutaneous wire-guided peritoneal drains

- 3 were managed with peritoneal drains alone, one of which also had a cystostomy tube due to failure to pass a urethral catheter

Median urethral catheter duration was 3.5 days (range: 2–6), and peritoneal drains stayed in for a median of 2 days (range: 1–5).

Urethral Ruptures

25 cases involved urethral rupture.

- 8 were treated with urethral catheters only

- 6 with cystostomy tubes only

- 10 with both

Of the 18 urethral catheters placed, 11 were passed retrograde (from the outside in), and 7 were placed antegrade via surgical cystotomy and hydrophilic wire guidance.

Urethral catheters remained in for a median of 6 days (range: 2–7), while cystostomy tubes stayed in for a median of 14 days (range: 5–58).

Again, this study only included successful cases, so we cannot conclude superiority over surgical repair.

How Does This Compare to Other Studies?

Let’s look at two additional retrospective studies.

Hornsey et al. (JFMS 2021) studied 53 cats with uroabdomen. About 25% were managed medically, with a 62% survival rate. In the surgical group, 78% survived. While the difference wasn’t statistically significant, the sample size was small and may be underpowered (type II error).

Grimes et al. (JAVMA 2018) reported outcomes in 43 dogs with uroabdomen:

- 6 were treated medically (5 survived)

- 37 underwent surgery (29 survived)

One particularly interesting case involved a dog that developed a uroabdomen 3 days after catheter removal. Instead of pursuing surgery, clinicians reinserted the catheter for another 8 days—and the dog recovered.

So even if initial conservative management fails, extended diversion may still work.

Taken together, these studies suggest that conservative management is a viable option in both dogs and cats—when the right conditions are present.

A Practical Clinical Algorithm

So how do you decide who’s a good candidate for conservative management?

There are no prospective studies comparing surgical versus medical therapy. But based on literature and clinical experience, here’s a structured approach:

Step 1: Stabilize the Patient

For unstable patients with suspected urinary tract rupture, don’t rush to surgery.

Stabilize first:

- Treat shock

- Correct hyperkalemia, acidosis, and electrolyte derangements

- Perform abdominocentesis or place a drain to reduce uroabdomen volume

Step 2: Confirm Diagnosis and Rule Out Sepsis

Perform:

- Cytology of abdominal fluid

- Effusion-to-serum creatinine ratio

- Effusion-to-serum potassium ratio

In Schmiedt et al. (JVECC 2001), creatinine ratio >2 had 86% sensitivity and 100% specificity; potassium ratio >1.4 had 100% sensitivity and specificity.

However, in Grimes et al. (JAVMA 2018), creatinine ratio >2 was supportive in 26 of 29 dogs (90%). The potassium ratio was supportive in only 8 of 14 (57%). Of the 6 dogs with confirmed uroabdomen and a potassium ratio <1.4, 4 still had a creatinine ratio >2. The other 2 were confirmed surgically despite both negative ratios.

Clinical takeaway: measure both ratios in all patients with suspected uroabdomen, but remember—neither is perfect.

Step 3: Identify the Leak Location

Leaks may occur in the kidneys, ureters, bladder, or urethra.

Urethral tears might not cause free fluid. In the RVC study, 6 animals with urethral tears presented with soft tissue swelling (scrotal, preputial, perineal, pelvic limb) or abscess.

Use imaging:

- Retrograde cystourethrogram

- Excretory urogram

- Contrast-enhanced CT

Step 4: Evaluate Defect and Patient Status

Ask yourself:

- Is the tear small and likely to seal?

- Is the tissue devitalized or completely transected?

- Can this patient tolerate anesthesia?

Small, iatrogenic tears (e.g., cystocentesis-related) may heal with medical management.

Large, devitalized ruptures usually require surgery.

Unstable patients may initially require conservative care—even if surgery is planned later.

Interestingly, Burrows and Bovee (Am J Vet Res 1974) showed that 3 of 14 dogs with surgically induced 3-cm bladder incisions healed without treatment, suggesting even large defects may self-resolve.

Step 5: Discuss Options with Clients

Conservative management is less invasive and faster to start, but it may mean longer hospitalization. That can be just as expensive—or more—than surgery.

In cats, especially with intrapelvic urethral tears, conservative care is often preferred due to difficult surgical access.

Step 6: Execute the Plan

Bladder rupture:

- Place a urinary catheter

- Add peritoneal drainage if needed

- If leakage resolves, abdominocentesis alone may suffice

- Preferred drains: wire-guided catheters (e.g., Mila chest tubes)

Urethral tears:

- Attempt retrograde catheterization

- If unsuccessful, try antegrade catheterization via cystotomy

- If both fail, place a cystostomy tube

Renal pelvic or ureteral rupture:

Manage with peritoneal drain ± urinary catheter to reduce hydrostatic pressure.

Step 7: Monitor and Reassess

Bladder injuries often sealed in 3 days (range: 1–6). Urethral injuries required longer—6 to 7 days. Before removing any devices, repeat imaging with contrast to confirm resolution.

If leakage persists, continue diversion or consider surgery.

Common Complications of Medical Management

Two main complications to watch:

1. Urinary Tract Infections

Particularly in urethral tears and long-term catheter use. In the RVC study, 14 of 22 previously uninfected patients developed UTIs—12 of them had urethral tears. Bubenik et al. (JAVMA 2005) showed a 27% per day increase in UTI risk with catheterization.

2. Urethral Strictures

These occurred in 11 of 25 urethral tear cases (44%) in the RVC study.

- 9 required urethrostomy

- 2 were euthanized

Median time to diagnosis was 12 days

Warn owners about this risk. If stranguria or incomplete urination develops, perform a contrast urethrogram to rule out stricture.

The Bottom Line

Conservative, non-surgical management of urinary tract rupture is a valid and evidence-based option in dogs and cats. It may help avoid surgery in selected patients—especially those with iatrogenic trauma, small lesions, or hemodynamic instability. Some studies show comparable outcomes to surgery, but close monitoring is essential, and we lack definitive trials to establish non-inferiority.

Author: Igor Yankin

Igor is the founder of VetEmCrit.com and a board-certified specialist in veterinary emergency and critical care. View all posts by Igor Yankin