A 7 year-old spayed female miniature poodle was referred to a veterinary teaching hospital emergency service for further evaluation of severe thrombocytopenia due to a suspected immune-mediated thrombocytopenia with a platelet count of 12k/uL confirmed by a blood smear. Initial work-up included standard bloodwork, a tick-borne disease panel, thoracic and abdominal imaging. No apparent underlying causes of presumed ITP were identified. An initial physical examination showed moderate tachycardia with a HR of 150/min, strong femoral pulses, pale mucous membranes and multifocal cutaneous petechiation. The dog was eupneic and had normal bronchovesicular sounds. There was melena on rectal palpation. The patient’s PCV was 20% with TS of 5.5 g/dl.

Based on the results of initial assessment, it was decided to perform a blood transfusion, start injectable steroid using an immunosuppressive dose, and give a dose of vincristine to hasten platelet recovery time (Rozanski et al, JAVMA 2002). The dog received 20 ml/kg of pRBCs in order to increase her hematocrit by 15%. The following formula was used to calculate the amount of blood to be transfused: 1.5 x desired rise in PCV (%) x BW (kg) (Short et al, JVECC 2012).

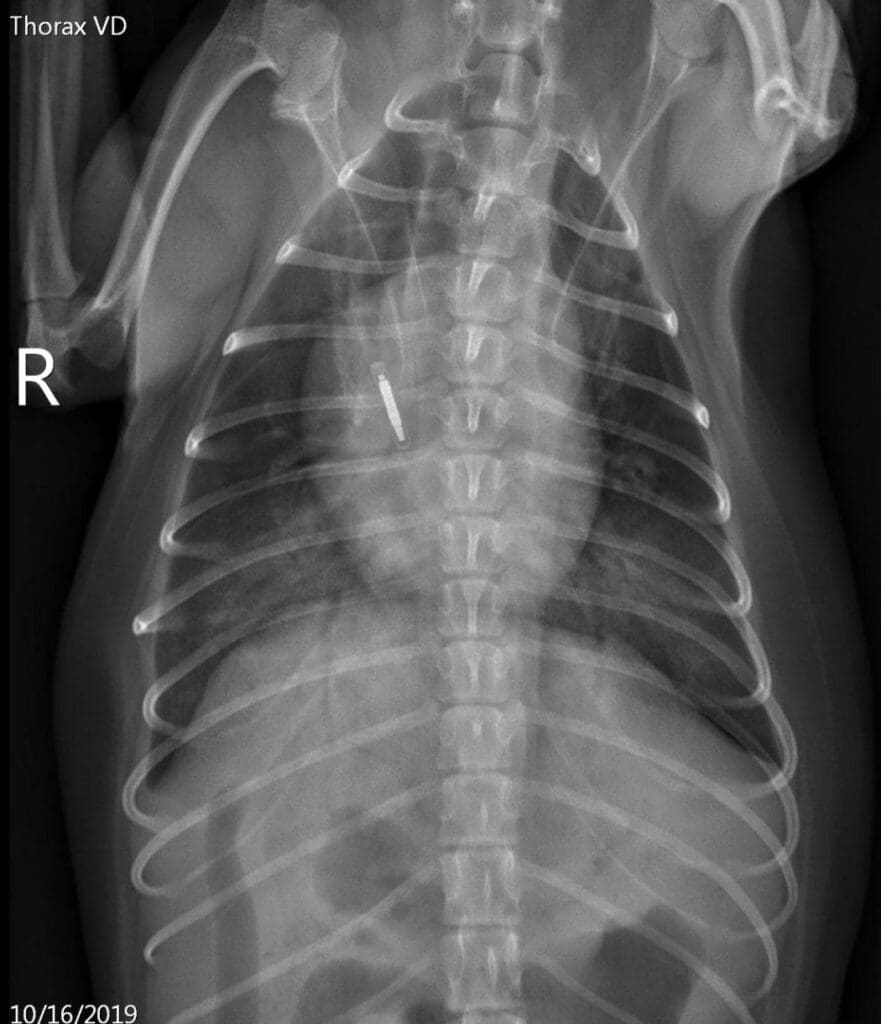

Three hours after the blood transfusion was finished, the dog’s respiratory rate and effort increased. Thoracic radiographs were performed to identify the cause of the patient’s changed breathing pattern (see below).

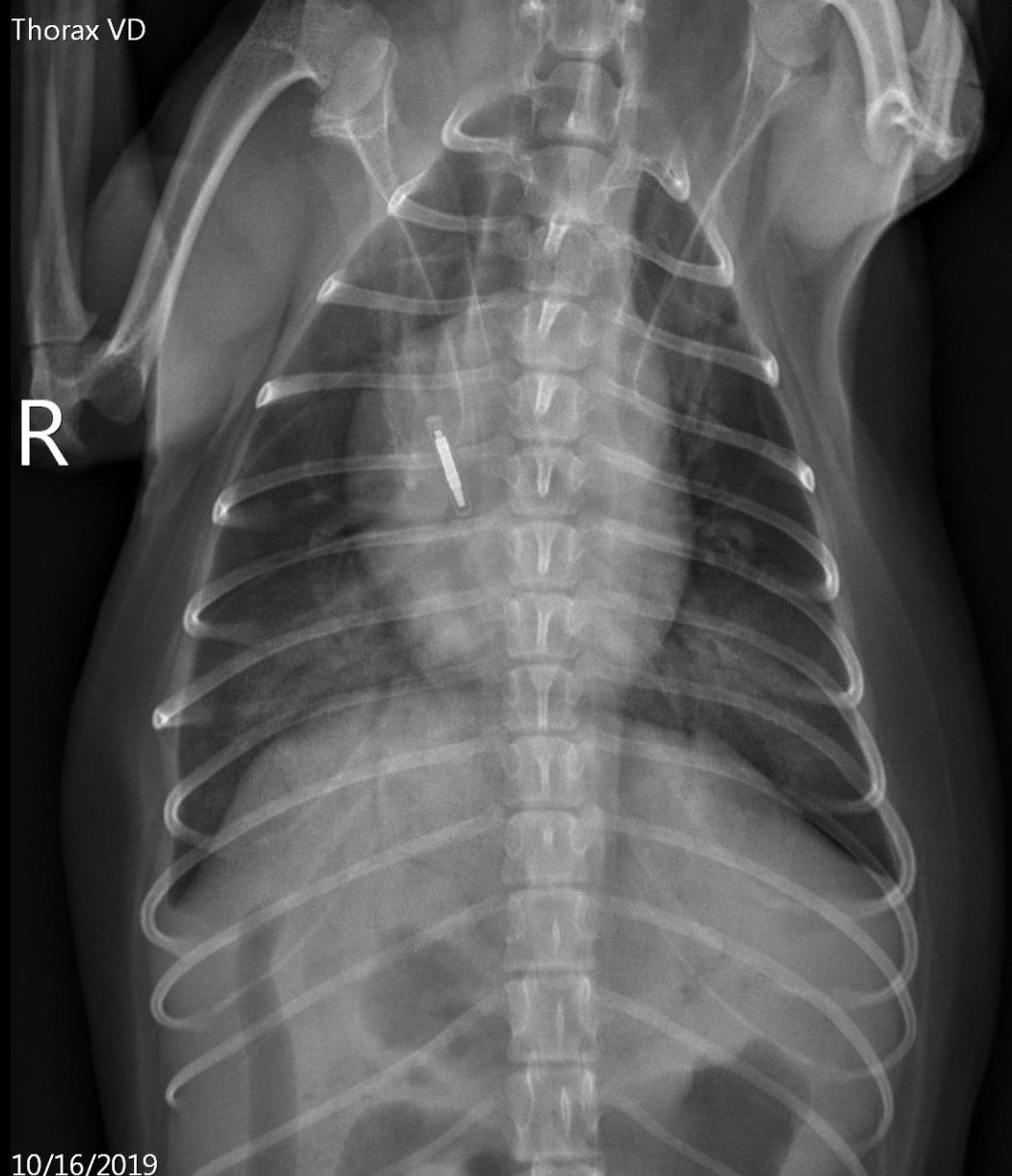

VD view of the thorax 4 hours after the blood transfusion

VD view of the thorax before the blood transfusion

Left lateral view of the thorax 4 hours after the blood transfusion

The following differential diagnoses were primarily considered in this dog (starting from the most likely diagnosis):

- 1. Classic TRALI (transfusion-related acute lung injury)

- 2. Pulmonary hemorrhage secondary to severe thrombocytopenia

- 3. TACO (transfusion-associated circulatory overload)

- 4. Vincristine-associated pulmonary toxicity

Due to the patient’s worsening dyspnea refractory to the oxygen therapy, the presence of respiratory fatigue and the owner’s financial constraints, a humane euthanasia was performed.

Discussion

Now, let’s further dissect this case and discuss our differential diagnoses one by one. Also, I will briefly talk about a potential management plan that could have been implemented if the patient had not been euthanized.

Classic TRALI

The definition of TRALI was based on the widely used definition of acute lung injury (ALI) proposed by the American European Consensus Committee, which includes bilateral alveolar infiltrates, hypoxemia (PaO2/FIO2 <300 mmHg), and the clinical exclusion of cardiac failure (Bernard et al, Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1994). For a diagnosis of TRALI to be made there must be no preexisting ALI before transfusion, the onset of the signs and symptoms must occur within 6 hrs of the transfusion and there must be no temporal relationship to alternative risk factors for ALI (Marik et al; CCM 2008).

Our patient had acutely-developed bilateral infiltrates, received a blood transfusion within 6 hours prior to the onset of clinical signs and was likely severely hypoxemic. No heart murmur or left atrial enlargement was evident on physical examination and thoracic imaging, therefore a cardiogenic origin of pulmonary infiltrates is deemed unlikely.

Due to the time frame when the respiratory distress has developed and the mentioned-above information, classic TRALI was a top differential in this case. A diagnosis of TRALI is relatively rare in veterinary medicine. One paper (Thomovsky et al, JAVMA 2014) showed the incidence of VetALI of 3.7% (2/54 dogs) that was significantly less than the reported incidence of TRALI in humans (25%) and not significantly different from the reported incidence of ARDS in ill dogs (10%).

Two theories have been proposed to explain the pathophysiology of TRALI. The first suggests that an antibody-mediated reaction after transfusion of anti-granulocyte antibodies into patients who have leukocyte that express the cognate antigens is responsible for TRALI. The second postulates that TRALI is mediated by an interaction between biologically active mediators in banked blood products and the lung (Toy et al, CCM 2005; Curtis et al, CCM 2006).

The treatment of TRALI is essentially supportive and may include oxygen therapy, positive pressure ventilation and conservative fluid therapy. In contrast to classic ALI/ARDS which has an associated mortality of approximately 40%, that of TRALI is estimated at between 5%–10% in people (Toy et al, CCM 2005; Curtis et al, CCM 2006).

Pulmonary hemorrhage

Pulmonary hemorrhage was another important differential diagnosis in this case since our patient had severe thrombocytopenia leading to suspect GI bleeding. It has been shown that dogs with melena secondary to ITP tend to have worse prognosis (O’Marra et al, JAVMA 2011). In the same paper, 5% of the dogs (4/73) developed respiratory distress attributed to pulmonary hemorrhage, pulmonary thromboembolism, or acute lung injury. Diffuse alveolar hemorrhage (DAH) secondary to severe thrombocytopenia has been reported in people (Keiki Nagaharu et al, Case reports in hematology 2019), however it is considered very rare.

Our institution carries lyophilized platelet products, and platelet transfusion was strongly considered in this case if the dog had not been euthanized. An addition of IVIG to already given vincristine could have potentially further facilitated a rapid increase in platelet count, however evidence that this type of combination therapy works better in veterinary medicine is lacking.

TACO

Transfusion-associated circulatory overload (TACO) is a transfusion reaction in which pulmonary edema develops primarily due to volume excess or circulatory overload. TACO typically occurs in patients who receive a large volume of a transfused product over a short period of time, or in those with underlying cardiovascular or renal disease. In our case, the dog received 20 ml/kg of pRBCs over 4 hours. There was no historical, clinical or radiographic evidence of cardiac disease before or after blood transfusion. Also, the clinical signs of respiratory distress developed 3 hours after the end of transfusion, which makes TACO even less likely in this particular case.

Vincristine-associated pulmonary toxicity

A case report published by Polton et al. (Vet J 2008) described a cat that developed dyspnea within 6 h of vincristine administration. Emergency therapy was instituted resulting in a full recovery.

In people, pulmonary toxicity has been well described when vincristine is used in combination with other chemotherapeutic agents. However, it is not generally believed to be the major contributing factor. A retrospective review of 207 patients with non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma treated with three different vincristine-containing regimens suggests that most likely methotrexate, but potentially also leucovorin and/or bleomycin, was the cause of pulmonary toxicity, not vincristine (Shapiro et al. 1991). When vincristine is used in combination with bleomycin, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, procarbazine, prednisone, and gemcitabine, 30% of 27 patients experienced serious pulmonary toxicity believed to be due to an interaction between bleomycin and gemcitabine. Neither radiation nor vincristine was believed to be a contributing factor (Macann et al. 2008).

To the author’s knowledge, there are no case reports documenting pulmonary toxicity in dogs secondary to a vincristine administration, therefore this diagnosis was less likely in this dog, however could not be completely ruled out.

Conclusion

TRALI and acute pulmonary hemorrhage were the most likely differential diagnoses in this case. Aggressive supportive care including high-flow oxygen or mechanical ventilation in combination with platelet transfusion could have been performed if the owner had not elected humane euthanasia. Based on available literature and personal experience, this dog had a decent chance to be saved.

References

1. Comparison of platelet count recovery with use of vincristine and prednisone or prednisone alone for treatment for severe immune-mediated thrombocytopenia in dogs; Rozanski et al, JAVMA 2002.

2. Accuracy of formulas used to predict post-transfusion packed cell volume rise in anemic dogs. Short et al, JVECC 2012.

3. Acute lung injury following blood transfusion: Expanding the definition; Paul E. Marik; CCM 2008.

4. The American-European consensus conference on ARDS: Definitions, mechanisms, relevant outcomes, and clinical trial coordination. Bernard GR et al, Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1994.

5. Incidence of acute lung injury in dogs receiving transfusions. Thomovsky et al, JAVMA 2014.

6. Transfusion-related acute lung injury: Definition and review. Toy et al, Crit Care Med 2005.

7. Mechanisms of transfusion-related acute lung injury (TRALI): Anti-leukocyte antibodies. Curtis et al, Crit Care Med 2006.

8. Treatment and predictors of outcome in dogs with immune-mediated thrombocytopenia. O’Marra et al, JAVMA 2011.

9. Successful Management of Immune Thrombocytopenia Presenting with Lethal Alveolar Hemorrhage. Keiki Nagaharu et al. Case reports in hematology 2019.

10. Pulmonary oedema as a suspected adverse drug reaction following vincristine administration to a cat: A case report. Polton et al. Vet J 2008.

11. Noncardiogenic Pulmonary Edema: An Unusual and Serious Complication of Anticancer Therapy. Briasoulis et al, The Oncologist 2000.