A 2-year-old spayed female standard poodle was referred to a specialty private practice for evaluation of a suspected small intestinal mechanical obstruction. Two weeks prior, the dog started vomiting and stopped eating. The initial diagnostic work-up performed by her primary veterinarian showed normal bloodwork, and the dog received regular supportive care on an outpatient basis. Due to the presence of persistent vomiting and inappetence, the abdominal survey radiographs were performed, and they were consistent with the gastrointestinal obstruction as it was interpreted by a board-certified radiologist.

Upon the transfer to the referral hospital, a full abdominal ultrasound was conducted, and it revealed evidence of focal small intestinal dilation that could be consistent with the original diagnosis, however no obvious foreign objects were identified within the gastrointestinal tract. After the discussion with the owner, it was elected to pursue medical management with the plan to repeat abdominal imaging the following day. In the next 48 hours, the dog received supportive care and two focal gastrointestinal ultrasound exams, both of which showed progressive severe focal dilation of the small intestinal loops when compared with the original study. Based on this information and persistent vomiting despite the use of multiple anti-emetics, the canine patient was taken to an exploratory laparotomy. Prior to the surgery, canine hypoadrenocorticism was ruled out by running a basal cortisol that came back as greater than 2 ug/dL (>55 nmol/L) (Bovens et al, JVIM 2014).

During the surgery, no evidence of mechanical gastrointestinal obstruction was identified but the surgeon noted a severe diffuse dilation of the small intestine without appreciable peristalsis. Multiple full-thickness biopsies of the entire gastrointestinal tract were obtained prior to the abdominal closure.

The histologic features of the gastric and small intestinal specimens were striking and were composed of mononuclear cellular infiltrate that targeted primarily the longitudinal and circular layers of the muscularis externa (leiomyositis). These lesions likely represented a manifestation of chronic intestinal pseudo-obstruction (also known as CIPO, myopathic type).

CIPO is a syndrome reported in dogs where impaired intestinal motility results in clinical signs of obstruction without mechanical occlusion of the intestinal lumen. Several causes have been identified and subclassified into developmental, infectious, inflammatory, autoimmune, metabolic, paraneoplastic, endocrine, and toxic etiologies. Leiomyositis has been identified as a cause of CIPO in dogs. In this condition the myofibers are targeted in what is likely an autoimmune disease. Infiltration of the smooth muscle by lymphocytes and replacement of muscle with fibrous connective tissue disrupts motility resulting in the clinical signs.

Zacuto et al. (JVIM 2016) described the largest case series of 6 dogs with confirmed CIPO. All of these dogs underwent exploratory celiotomy due to suspected mechanical obstruction secondary to a foreign body. One of these dogs had an abdominal CT scan performed 11 days postoperatively because mechanical obstruction was suspected again, and the abdominal ultrasound exam was consistent with intraluminal foreign material. The CT scan allowed visualization of the luminal contents of all dilated bowel loops without obstructive material, further refuting the presence of mechanical obstruction. As a result, the CT scan prevented a second exploratory laparotomy being performed on the dog. The authors recommended that an abdominal CT could be used as an adjunctive imaging modality, particularly in large breed dogs with gas distended intestinal loops, in which abdominal ultrasonography had important limitations. The median body weight of canine patients in that case series was 30.4 kg (range, 19.7–38.7 kg).

Leiomyositis affecting extragastrointestinal organs is becoming an increasingly reported entity in humans and dogs. In a case series published by Zacuto et al., one of the dogs initially presented with protrusion of the nictitating membrane, and histopathology confirmed leiomyositis of the third eyelid (!).

The prognosis of dogs with intestinal leiomyositis is generally poor with survival times ranging from 10 days to 5 weeks after diagnosis (Zacuto JVIM 2016; Lamb AVJ 1994). Too few cases are present in the literature to identify a breed or age distribution.

Management of CIPO in people is extremely challenging and is predominantly aimed at controlling symptoms and minimizing complications (Antonucci World J Gastroenterol 2008). Prokinetic treatment is a mainstay of treatment with cisapride being most commonly used. In dogs, it has been shown to increase lower esophageal sphincter pressure and decrease gastroesophageal reflux. Immunosuppressive agents (e.g. prednisolone, cyclosporine, azathioprine) have been used in humans with documented intestinal leiomyositis as well. The best results have been achieved early in the disease process (Antonucci World J Gastroenterol 2008). In human patients with severe CIPO refractory to medical treatment, near total small bowel resection can be an effective treatment to relieve clinical signs and improve health and quality of life, although such patients remain dependent on home parenteral nutrition (Lapointe J Gastrointest Surg 2010).

Back to our patient…

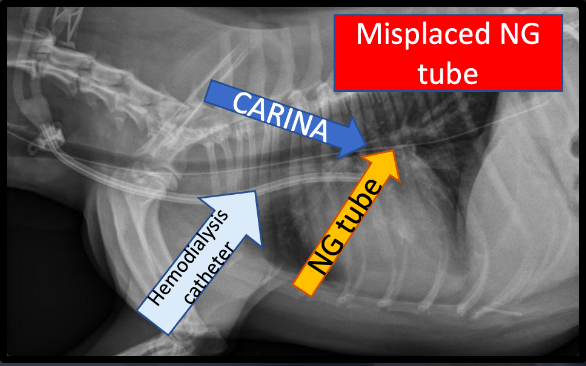

The canine patient described earlier in this blog article continued her hospitalization for the next 7 days. She received aggressive supportive care that included fluid therapy, NG tube feedings, multiple prokinetics, anti-emetics, and gastroprotection. On day 5, she developed severe aspiration pneumonia and received an antibiotic therapy. The dog continued to have persistent vomiting, regurgitation, diarrhea, anorexia and labored breathing. The owner elected humane euthanasia after 10 days of hospitalization due to the lack of any improvement and progressive respiratory distress.

The Bottom Line

CIPO is a rare syndrome in dogs that small animal practitioners should bear in mind. Medium to large breed dogs may be overrepresented. CT could be used as an adjunctive imaging modality in dogs with suspected CIPO or equivocal abdominal ultrasound results. Gastrointestinal biopsies should be strongly considered in all cases of negative exploratory laparotomies due to suspected mechanical GI obstruction.

References

- Bovens C, Tennant K, Reeve J, Murphy KF. Basal serum cortisol concentration as a screening test for hypoadrenocorticism in dogs. J Vet Intern Med. 2014 Sep-Oct;28(5):1541-5. doi: 10.1111/jvim.12415. Epub 2014 Jul 28. PMID: 25066405; PMCID: PMC4895569.

- Zacuto AC, Pesavento PA, Hill S, McAlister A, Rosenthal K, Cherbinsky O, Marks SL. Intestinal Leiomyositis: A Cause of Chronic Intestinal Pseudo-Obstruction in 6 Dogs. J Vet Intern Med. 2016 Jan-Feb;30(1):132-40. doi: 10.1111/jvim.13652. Epub 2015 Nov 26. PMID: 26608226; PMCID: PMC4913632.

- Antonucci A, Fronzoni L, Cogliandro L, Cogliandro RF, Caputo C, De Giorgio R, Pallotti F, Barbara G, Corinaldesi R, Stanghellini V. Chronic intestinal pseudo-obstruction. World J Gastroenterol. 2008 May 21;14(19):2953-61. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.2953. PMID: 18494042; PMCID: PMC2712158.

- Lamb WA, France MP. Chronic intestinal pseudo-obstruction in a dog. Aust Vet J. 1994 Mar;71(3):84-6. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-0813.1994.tb03334.x. PMID: 8198514.

- Lapointe R. Chronic idiopathic intestinal pseudo-obstruction treated by near total small bowel resection: a 20-year experience. J Gastrointest Surg. 2010 Dec;14(12):1937-42. doi: 10.1007/s11605-010-1295-7. Epub 2010 Sep 25. PMID: 20872085.